July 1925 - December 1970

Gus Wilson's Model Garage

Alphabetical List of Stories Monthly Illustration Galleries Index Links-All Stories

September 1925

THE TRICKS IN SHIFTING GEARS

by Martin Bunn

Gus, the Expert Mechanic,

Gives Some Sound Advice to the Beginner

Who Comes to Grief on a Hill.

Gus Wilson, half owner and chief mechanic of the Model Garage, always claimed that he could tell by the sound of the telephone bell when the party at the other end of the wire was in serious difficulties. It was not strange, then, that he chucked a wrench back into the toolkit and stood up with a yard-long scowl on his face as the telephone rang sharply and insistently. The ringing stopped abruptly, and a few seconds later Joe Clark, his partner, popped out of the office where he kept track of customers' accounts and did the bookkeeping.

"Ding bust it!" exploded Joe. "Al Taylor from Ridge Street has got himself all mussed up down at the bottom of Smoke Hill and he wants to be hauled in right away. Can we make it?"

"Make it?" said Gus, disgustedly. "Sure we can, but how about this job for Mrs. Jenkins? You know we promised it this morning. Can you lay off those bills long enough to -- ."

"Sure," grinned Joe. "That's where I shine as a mechanic -- finishing up jobs when all hard work is done."

Gus answered with an unintelligible grunt, cranked up the wrecking truck, and rattled out of the garage with the mudguards flapping like the wings of a bedraggled and much frightened chicken. The wrecking truck was built for service, not for looks.

Smoke Hill, about three miles south of town, was commonly spoken of by motorists as a "cork-puller."

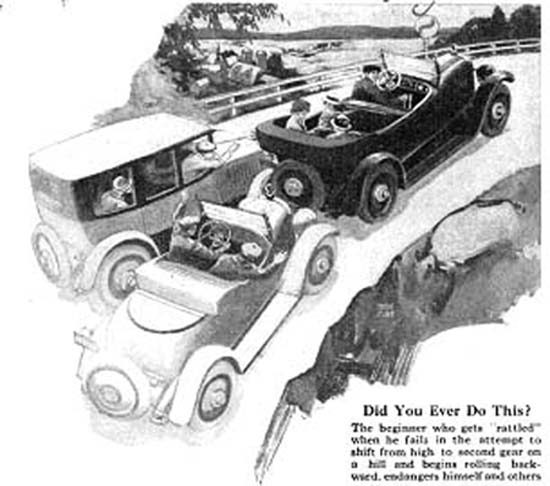

A sharp turn at the bottom prevented any chance of rushing the grade, which was mild enough for the first hundred yards. And the ease with which this part of the hill could be negotiated proved the undoing of the inexperienced motorist, for it became gradually steeper and steeper until, near the top, the grade was so stiff that few cars could make it without changing to second or even first.

Gus found Taylor about halfway up the hill. His car was off the road and the smashed mudguard and broken rear wheel jammed against a large oak tree testified mutely to the cause of the accident.

The unlucky motorist rushed over to the truck as Gus applied the brakes and began volubly and excitedly to explain just how it happened.

"No need to go into details, Mr. Taylor. I can see how you got into trouble," interrupted Gus. "This is where you would have to shift into second. I suppose you got rattled and couldn't get the gearshift."

Taylor appeared surprised and a bit crestfallen.

"Then it was my fault? Gosh, I thought something had gone wrong with the transmission, and I was so rattled I never thought to put on the brake until it was too late. I suppose I'll have a nice, fat repair bill," he added ruefully.

Gus backed the truck into position to hoist the rear end of the car preparatory to towing it.

In a few minutes the two men had everything shipshape, and when Gus cranked the winch, the rear end of the damaged car left the ground on a perfectly even keel.

"Tell me, Gus, what did I do wrong?" Taylor asked as they drove carefully down the hill in the direction of town.

"Well -- no offense meant, Mr. Taylor -- but you are a new driver, and almost everything a new driver does is wrong. The thing you did is one that often trips up the man who hasn't had a whole lot of experience."

"Go on," said Taylor, "you can't hurt my feelings. I thought I was the real thing as a driver. Now I know I'm not; so go right ahead, and maybe next time I won't be so dumb."

"You see, Mr. Taylor, gear-shifting is mostly a matter of practice and knowing what happens inside the transmission case when you work the lever," said Gus. "Also cars are just like horses. You must be wise to the particular whims of the critter you happen to be driving because no two are exactly alike. That's why a man who can handle one car in fine style often makes noises like a beginner when he is driving another make."

"Huh," said Taylor, a bit peevishly. "Nobody can say that I can't shift gears quietly! I snap 'em in before they get a chance to grate!"

"Sure," Gus went on; "and that is just where you make your big mistake. You 'snap 'em in ,' as you say, without any regard for the relative speeds of the gears you are trying to get into mesh, and everything goes fine and dandy until you get caught because the difference in speed is too much. Then they simply refuse to snap in, and you end up by trying to push over a two-foot tree. You ought to be thankful the tree was there to stop you. You might have had a doctor's bill to pay in the bargain!"

Taylor shivered involuntarily.

"That's a pleasant thought," he said, more humbly. "Go on -- I haven't any right to be proud."

Gus said nothing for a few seconds, for they were approaching a crossing and the wrecking truck with its trailing load claimed his undivided attention.

"Look at that fellow there who is waiting for the trolley," he exclaimed suddenly.

"Watch him when he tries to jump on. See, he stood still and the trolley nearly pulled his arm out by the roots."

"There's a good example of what happens when you try to shift gears by snapping them in. If the speeds of the two gears are somewhere near alike they go in with a jerk. If they are not, then they won't go in at all, and that's what happened to you. That man who hopped the trolley could have saved himself the yank on his arm if he had turned and run in the direction the car was going."

"You know, of course, that with the lever in first gear the motor in an automobile turns over much faster in proportion to the speed of the car than when the gears are in high. Now, when you throw out the clutch, the motor is disconnected from the gearbox, but the section of the clutch that is fastened to the gears just naturally keeps on turning. That means you have to figure out some way to slow it down when you are shifting from a lower speed to a higher one, or to speed it up if you are changing from a higher speed to a lower one."

"Sounds familiar," said Taylor, smiling. "The man who taught me how to drive used to run off a talk something like that, but I never could understand how to apply it to driving an automobile."

"All right, then," Gus answered, "let's put it in a rule-of-thumb way. Just remember one simple rule: Take your foot off the throttle when you shift to a higher gear and keep it on when you shift to a lower one. This works on most cars, because the slight drag in the clutch makes the free part of it speed up or slow down with the engine. If you remember that one simple rule, then all you have to watch out for is the time interval, and you can get that by practice. "Of course, it doesn't make any difference to other automobilists on the road whether you tear the whole transmission out or not, so long as you are on level ground, but if you are on a steep hill, it's another story. Suppose there had been a bunch of cars right behind you today!"

"Oh, don't rub it in, "said Taylor. "I'm a muttonhead all right. But suppose you just show me how it ought to be done on this hill we're coming to. Then maybe I can get it through my head right."

"Good idea," said Gus. "Now you watch carefully. I'll have to shift into second about 100 feet from the bottom."

Taylor kept his eyes glued on Gus's feet. When the engine began to slow up, down went the left foot on the clutch pedal just far enough to disengage the clutch, and almost simultaneously the gear lever went into neutral. The right foot remained on the throttle and when the motor had attained just the right speed. Gus eased the lever into second and released the clutch pedal without a suspicion of clash or jerk.

"Gee, that was as smooth as silk," said Taylor admiringly. "It looks like nothing at all the way you do it."

Gus's wrinkled face creased in a smile.

"Just like everything else, Mr. Taylor; it's easy when you know how. As far as auto transmissions go, you can make one last at least twice as long if you treat it right."

A few minutes more and they were in the garage, and Gus busied himself arranging blocks so that the axle would be supported when the car was lowered.

"How soon will the old boat be ready again?" Taylor asked.

"Well," said Gus, with a quick glance around the garage to check up on the jobs that should be finished before Taylor's, "about Thursday afternoon, I guess -- yes, I'll promise it by then. I suppose you will steer clear of Smoke Hill after this," he added, with a twinkle in his eye.

"No, sir!" said Taylor. "I'm going up that hill if it's the last act of my life!"

"Better get in some practice on level ground first, then," said Gus; "and, by the way, Mr. Taylor, if you really want to get into the expert class as a driver you might like to know how to do the 'double clutch'"

"I'll bite," said Taylor, looking puzzled. "What is it -- a joke?"

"Double clutching is no joke," answered Gus. "It's something that most auto drivers know nothing about, yet it certainly is a good thing to know if you happen to want to make the other fellow eat the dust on a bad hill."

Taylor was interested immediately. "Fine!" he said. "Give me all the dope on that. I never did like the taste of dust anyway!"

"I don't know whether I ought to tell you or not, seeing as how you haven't mastered the regular way of shifting gears yet," Gus began. "However, if you'll promise not to blame me if you rip out the transmission trying it, I'll explain double clutching."

"Remember how I shifted into second on that hill? You noticed, of course, that I waited till the old bus had slowed down quite a bit before I tried to shift. Now, if you were trying to race a man up that hill, you naturally wouldn't want to wait till the car slowed down; you would want to make the shift while the car was still going good and fast."

"The only way you can drop from high into second when you are going fast is to use the double clutch. Otherwise you would be almost sure to make a lot of grinding noises."

"Here is how you do the double clutch. The minute the car starts to slow down in high, jam your foot on the clutch pedal and throw the gear-shift lever into neutral. Keep the accelerator pressed down hard. Of course, the second the clutch is thrown out and the load of the car is taken off, the motor will start to race to best the band. With gearshift lever still in neutral, let the clutch in quickly, push down on the clutch pedal again right away, then immediately throw the speed lever into second and let the clutch in again."

"What happens is that while the gear lever is in neutral, the gears you intend to mesh are speeded up by letting the clutch in so that when you push out the clutch and throw her into second there will be practically no clash. That is, if you get the timing right. The only way you can get that is to practice."

Taylor threw up his hands in despair.

"Gosh!" he exclaimed, as he turned to go: "nothing doing on that for me. Guess I'll stick to plain driving. I can't afford a new transmission just for the pleasure of beating some bird up a hill."

"Drat it!" mumbled Gus to himself as he stared after Taylor's retreating form. "Say, Joe, why is it that every bird who succeeds in scraping through the driver's examination decides right away that he is the real thing as a driver and tries to navigate around in heavy traffic just like an old-timer?"

"It would be a lot better for him and for the other fellows on the road if he would spend a lot of time on lonely roads practicing gear shifting and maneuvering the car until he really knew how to do it right."

END