May 1932

NEW CONTROLS

add airplane thrill to safe motoring

by Martin Bunn

"I've decided to stick to this old bus for a while longer, Gus," Barnly announced as he stopped his car in front of the Model Garage.

"Gus Wilson, half owner of the establishment, unlimbered the gasoline hose.

"New cars haven't enough style for you, eh?" he smiled as he turned the crank.

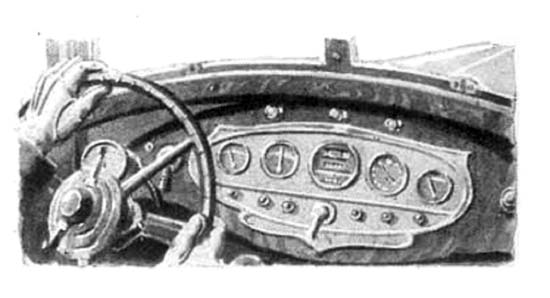

"Style!" Barnly exclaimed. "I wasn't thinking of that. What I'm kicking about is the fancy complications. What's the use of making an instrument panel with as many knobs, dials, and gadgets as radio sets had in the days when tuning one of them was a skilled occupation?

"Now you take this car of mine, for instance. Just a switch for the lights and a knob for the choke, the speedometer, oil gage, and ammeter, and there you are, all neat and shipshape."

"It does seem funny when you put it that way," Gus agreed. "The point is, of course, that most of the new controls operate things the old cars didn't have."

"It's all wrong," maintained Barnly. "Years ago they predicted that some day everything would be automatic in an automobile. All you'd have to do would be to steer and work the throttle, with the throttle fixed so when you took your foot off it, the brakes went on automatically. Millions of cars have been made since then and the more that are made the further they are from simplicity.Where's the fun in driving if you've got to keep your eye on half a dozen dials instead of the scenery and keep thinking about which knob you've got to press next, instead of about what a good time you're having? These fancy new features are a lot of bunk!"

"Humph!" Gus growled, "I suppose you'd rather run out of gas than take a look now and then at a gage on the instrument board that'll tell you exactly how many gallons you have left. Or maybe you'd rather put your motor on the blink through lack of water rather than look at a motor temperature gage once in a while?"

"I don't object to the extra gages so much," said Barnly. "They're some use. But how about the knobs you have to pull?"

"What car are you talking about?" Gus asked. "Some have the free wheel lock-out on the dash so you pull a knob when you don't want free wheeling. Some have an adjustment on the dash for the shock absorbers: and there may be knobs to turn on the windshield wiper, change the adjustment of the carburetor mixture, open some of the ventilators, and so on.

"At any rate," he continued, "you don't have to do anything with any of the knobs unless you want to. If you're satisfied to take an average adjustment for everything, you can set the knobs that way and forget them.

"Next as I can figure, it works out about like this: Years ago, before the self-starter was invented, automobiling was a sporting proposition. Hardly any women drove cars and the men who did had to have a good right arm to spin the motor and enough mechanical brains to fix the ordinary small troubles you ran into on the road. In those days there wasn't always a gasoline pump in sight and a service station in every town and hamlet. You had to know how to get along by yourself or wait for some other motorist to stop and help you.

"Then came the self-starter and everybody took up driving. The majority of the new owners hadn't the faintest notion of auto mechanics, so naturally the makers tried to get everything as simple as possible. Now the years have brought a change. A new generation has grown up and words such as 'carburetor,' 'cylinders,' 'pistons,' and 'spark plugs' don't seem like a foreign language any more. Maybe the average driver today isn't a mechanic, but at least he's got a glimmering of what it's all about."

"Is there anything in this free wheeling Gus?" Barnly interrupted, "My car rolls easy enough now, so what good would it do to make it roll any easier?"

"Have you driven a free-wheeling car?" Gus asked. "If you haven't the quickest way to find out is to take a demonstration. Of course the saving in gasoline they talk about isn't very important, the big thing is the acceleration you get. There's a sort of airplane feel about it. The car just floats along when you take your feet off the throttle and you don't get that tired-down, dragging effect of the throttled motor."

"What's the 'wizard' control I hear about?" Barnly asked. "Do you have to be a magician to operate it?"

"No magic about it," Gus said. "I suppose they called it 'wizard' because it's easier to say than vacuum operated clutch throw-out interconnected with the throttle, which is what it is. It's another way of getting free wheeling and it has its advantages, too. Under the floor boards is a short, fat cylinder with an air-tight piston hooked to the clutch pedal. A hole in the opposite closed end of the cylinder is piped to the intake manifold through a valve worked by a little pedal to the left of the clutch and also through another valve that is tied to the throttle pedal. It's set so that if your foot is resting on the pedal to the left of the clutch and you take your feet off the throttle, the vacuum of the manifold opens the clutch and you coast along just as you would if you'd pushed down the clutch pedal.

"When you step on the gas again, that shuts off the manifold vacuum and the clutch automatically takes hold. It's simple enough because if your left foot isn't pressing down the small pedal to the left of the clutch -- and the spring is so light the weight of your foot does it -- you get regular operation. With your foot resting on the pedal you get free wheeling."

"That sounds simple enough," Barnly cut in. "Now tell me what all this talk about silent shifting amounts to. I can shift gears now so you can't hear 'em. Why do I need any extra fancy business?"

"A lot of people I know do need it," Gus growled. "Still, I think you'd like a transmission of that kind because you don't have to watch your timing so carefully. There are several different arrangements. Cars that have an overrunning clutch to get the free wheeling, and most of 'em are that way, don't have to do so much to get silent shifting. When you take your foot off the gas pedal on a car like that, the overrunning clutch releases and the whole transmission slows down with the engine just as it would in an ordinary car when you slow down the whole car. It's no trouble to shift into second or even first from high in an ordinary car when it's just barely rolling along."

"How does an overrunning clutch make that possible?" Barnly asked. "I'm a bit leery about how it works. Is it some new mechanical principle?"

"I should say not!" Gus replied. "Overrunning clutches of many different kinds have been used on machinery for years and years. An overrunning clutch is any type of clutch that works only one way -- in other words, that holds two shafts only when the strain comes in one direction."

"Like a turntable, eh?" Barnly observed. "Turns free one way but locks the minute you try to turn it the other.

"Well, I used to get a lot of fun out of twiddling the dials on my old radio set trying to get distant stations loud enough to hear 'em, so maybe I'd get some fun out of driving a new car once I found what all the controls were supposed to do."

"I think you will -- most people do," Gus agreed. "After all, a man likes to feel that he's really running the car, and the controls help to make him feel that way."

END

L. Osbone 2019